If you are using the runes or practicing any form of Germanic paganism in the United States right now, you can thank Edred Thorsson —

and you should. Writing under that name or his birth name, Stephen Flowers, he’s been advancing the light of what he sometimes refers to as “The Northern Dawn” since the 1970s. He’s studied and has in many cases translated and republished the works of the early 20th Century runologists that others draw from. He founded

The Rune-Gild in 1980 to promote the study of the runes and has formed, served or advised several significant American pagan organizations. If you’ve said a sumbel or cast a rune or performed any kind of heathen rite, its form and content were probably influenced in some direct or indirect way by Thorsson.

Here are a few of his books that I’d recommend to anyone interested in Germanic paganism or runology:

The Northern Dawn – A History of the Reawakening of the Germanic Spirit

History of the Rune-Gild – The Reawakening of the Gild 1980—2018

The Nine Doors of Midgard

Futhark – A Handbook of Rune Magic

Runelore: The Magic, History, and Hidden Codes of the Runes

ALU, An Advanced Guide to Operative Runology

Rune Might – The Secret Practices of the German Rune Magicians

The Secret of the Runes by Guido von List (as translator and editor)

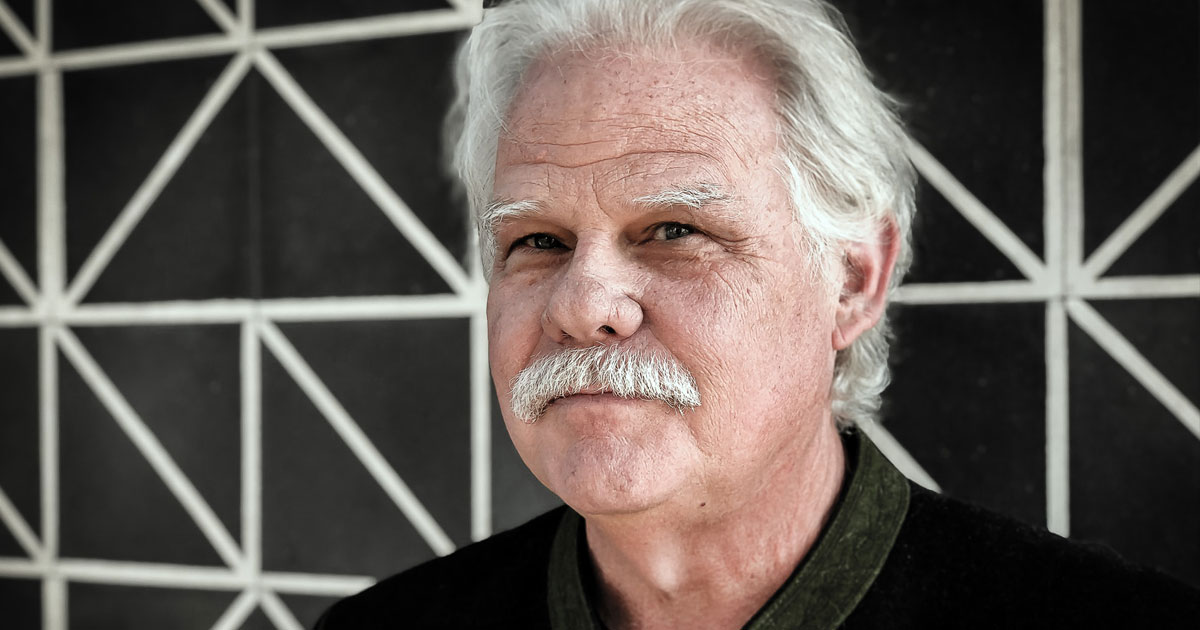

Thorsson’s Futhark and Runelore were two of the first books I ever read about runes. I was headed to Texas on business, and I wanted to meet “the man.” After reaching out to him through a mutual friend, I booked a table to meet him for lunch at Le Politique, a brightly-lit brasserie in downtown Austin.

I checked in with the hostess and ordered myself a Negroni. Then I noticed a white-haired man outside on the street. He was wearing a wool alpine jacket.

“Ah…that’s the guy.”

I went out to introduce myself.

It immediately became clear that Edred isn’t another dour occultist who relies on spooky posturing and an empty panne velvet bag full of “hidden secrets.” He’s energetic — animated by a sense of purpose. He’s full of ideas and information — so much information — but he’s also extremely modest. I deferred to him, calling him a scholar and describing myself as a mere “popularizer,” but Edred — who does have a PhD in Medieval Studies — insisted that he was a popularizer, too. I got the sense that he’s a man who found something that he’s passionate about, and he wants to share it with anyone who has eyes and ears for it. But he also wants to make sure they get it right.

We talked through lunch and into the beginning of the dinner shift about the business of writing, the runes, ritual, sacrifice, and the trials associated with organizing people. We talked about Jung and Nietzsche and Eliade. His observations and advice were sharp and extremely insightful. He’s been there and done a lot, but seems unexpectedly open-minded — still “seeking the mysteries.”

I enjoyed our informal conversation too much to take notes, so the following interview was conducted via email after the fact, riffing on of some of the topics we discussed over lunch.

JD: Your life seems to have been guided by a very clear sense of purpose, and you’ve been an extremely influential figure in a lot of people’s lives. What are some of the accomplishments that you are most proud of, and what qualities did you cultivate in yourself that helped you achieve them?

ET: My initiatory life was begun with the hearing of the word RUNA in the summer of 1974. It would be a misunderstanding of the whole process to believe that the subsequent journey was one that was “planned” — the whole process has been rather multi-dimensional. There has been a clear sense of moving forward and seeking the goals of learning to understand the mysteries of the Germanic (and Indo-European) cultural and intellectual realm, to facilitate the (re-)development of the values of our ancestral past in the modern world and in so doing make the world a better and more vigorous place. But as to the question of the things which I have consciously cultivated in myself to achieve these goals they are these: love of learning and curiosity about the next discovery, discipline necessary to learn the hard things (e.g. learning key languages, mastering the historical and philosophical contexts for all information to have a matrix of meaning, development of a pattern of work which facilitates the production vision and the will to see the envisioned products come to fruition). Most of these things were greatly aided in my development by the years-long experience in graduate school and the instilling in me an intellectual work-ethic by my professor, Edgar Polomé. Accomplishments of which I am proud are the body of written work which I have produced, the establishment of the Rune-Gild and the earning of a Ph.D. from a major university. These are all the results of inner tools developed on an esoteric level, and are all keyed to an unwavering dedication to the imperative: reyn til rúna (“seek the mysteries”).

JD: 1974. That’s the year I was born. “Seek the mysteries” is a truly Odinic motto. Some people are naturally curious and inventive. So many more want step-by-step instructions for everything. Anything worth doing probably involves hard work and some process of personal discovery — some kind of “gnosis.”

I read your History of the Rune Gild (Arcana Europa 2019). It’s a real page-turner. One comment struck me in particular. We discussed it briefly in Austin. You wrote:

“During that year I continued to be involved with the theories and practices of magic(k) and to explore an eclectic path generally of my own making. I couldn’t give much credence to the Wiccan form of “magic” at this point because it emphasized—in accordance with its essentially religious worldview—a harmonizing of the will of the individual with the patterns of nature. I had made the essentially magical and individualistic philosophy I had experienced earlier too much a part of myself to find this very attractive.”

This seems to me a major point of philosophical difference between many approaches, religions and ideologies. Can you elaborate on what you meant by this?

ET: Among the Wiccan neo-pagans I was acquainted with the early 1970s in Austin — and this was a time when the coven I was around was rife with rumors that the might be another coven in the area! — the attitude seemed to be that one was more “advanced” measured by the degree to which one was fully in harmony with the “cycles of nature.” These cycles determined one’s mood, success and so on. At first that just seemed to strike me wrong. I had been an enthusiast for the philosophy of Anton LaVey before this, and liked to say that when I thought of “nature” I thought of a thunderbolt, not a “daisy.” I dubbed the Wiccans “daisy sniffers” in my private jargon. I would have had to admit that at that time I did not know why this was so, I did consider the idea that the pagans of old were in some sense nature worshippers to be true. It would first be under the guidance of Professor Edgar Polomé that I would learn that, as he put it one day: “The Germanic peoples were not nature worshippers.” This was not just a statement, it was the conclusion to a long set of substantiated observations about Germanic (and by extension Indo-European) attitudes toward the mind, culture and the place of these categories within nature. The mind of man not only allows, but demands that humans act in ways contrary to nature, to transcend it, not “harmonize” with it (i.e. be its thrall). We learn from nature, and we learn when and where to act in accordance with natural conditions in order to succeed on a tactical level, but our overall strategy is one that aims for freedom and independence from naturally imposed limitations. The oldest myth in regard to this is reflected in Odin’s observation of the “natural world” into which he was born, governed by Ymir, and his rejection of it. He overthrew that order, sacrificed Ymir and remade the “natural” cosmos in the form of a rational and beautiful, mind-crafted replacement— in world in which we now live.

JD: Modern Germanic pagans have traditionally sought out “natural” environments in which to practice and perform ritual, perhaps influenced by these lines from Tacitus:

“The Germans, however, do not consider it consistent with the grandeur of celestial beings to confine the gods within walls, or to liken them to the form of any human countenance. They consecrate woods and groves, and they apply the names of deities to the abstraction which they see only in spiritual worship.”

However, later sources also describe lavish temples such as the Hof at Gamla Uppsala.

There’s something distinctly primal about holding ritual out under the trees and the open sky around a roaring fire. I was able to purchase land to build my sacred space, Waldgang, but to get some privacy and a few acres at a reasonable price, I had to move several hours away from any urban hub. It will become increasingly difficult for pagans to organize and finance these spaces as the world gets more crowded, as cities sprawl out and real estate becomes less affordable.

These concepts are eternal and elemental. As men continue to “transcend nature” can you imagine Germanic pagans practicing in urban spaces — or for that matter, even in space? How would you incorporate elements of this ancient practice into completely man-made spaces?

ET: The reason why natural environments, and often remote and secluded environments were seen as suitable for sacred activities are many. One they are separate from ordinary life and far away for the mundane activities of normal activities. This idea of being set apart is fundamental to the conception of the sacred, which means something separated from the ordinary. Natural settings were often chosen because of their special characteristics, a waterfall, a deep grove, a special rock formation, etc. all of which again set the place apart from the ordinary. It is in these environments that the ancients believed the holy was made manifest. Also, because festivals involving the whole tribe may require more space than could normally be accommodated in a hall or building (although extremely huge foundations of such buildings have been found in Scandinavia). The temples, such as the one mentioned at Uppsala was actually quite small and probably served as an inner sanctum for a larger holy complex in the area. All that being said, I do not see any prohibition against using elaborate temples or shrines. Religion and cult is constantly evolving. The important thing is that the sacred space is a place set apart and made special for the activities of the sacred and holy. The same observation that was made by Tacitus was also made by the Greeks and Romans about the Persians, who certainly built elaborate buildings, but whose most sacred spaces remained remote and natural regions. Conversely, the most every-day sacred space is most often just a corner of the house for a small household shrine. The holy is found in the extraordinary, and in the everyday.

JD: You’re working on a book about re-tribalization. To begin, what does the word “tribe” mean to you? It’s become a popular buzzword for marketers, and everyone with an email list or a social media group seems to believe they have a “tribe.” What differentiates a legitimate tribe from something like that in your mind?

ET: Indeed, the word “tribe” is often misused, or used in a way that detracts from the original scope and power of the institution being referred to by the word. Longing for a sense of tribe is an admirable impulse and a positive one. But we should not be satisfied with half-measures when it comes to this topic. The main confusion comes in between the concepts the actual tribe (German: Stamm) and a band or company (German: Männerbund). These are the two main alternative ways of organizing, and they often work together and complement each other. A band is entered into by individuals on a voluntary basis and each band (company, order, guild, etc.) has a specific purpose or craft which it pursues. A tribe is generally entered into by families and has as its purpose the protection and promotion of the interests of the members of that tribe. Traditionally one would be born into his tribe. Other ways of entering a tribe are by marriage, adoption or blood-brotherhood. In today’s jargon bands are often called tribes. This leaves the actual idea of the tribe out in the cold. A tribe would have to be made up of people who live close to one another, who interact on a very regular basis and who are bound to help and render aid to other tribe members. Tribes cannot exist on the Internet or by mail-order. This tribal organization can and will make the lives of every individual within it richer and happier. For millennia, we were organized as tribes, only recently, with the advent of the nation state has this mode of life been forgotten. This is one of the deep roots of or discontent as a people. Re-tribalization is the subject of my new book Re-Tribalize Now!, which is a guidebook to the idea. Re-tribalization is the best form of radical revolt against the Modern World. In is a non-violent form of rebellion, which is the only kind that is likely to succeed. If the Modern World is all about atomizing the individual, separating him from his cultural context in order to be able to manipulate him at will by marketers/politicians, then re-tribalization, by restoring the individual to his cultural roots and context in a profoundly structural way will blunt the detrimental effects of Modernization.

JD: When we were discussing the concept of tribe over lunch, you said that ideally, being part of a tribe should make life easier and better for the people in it — not harder. Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

ET: Often “tribal” life might be dominated by autocratic leaders or ideologies which make hard demands on the mind and conscience of individuals. “Tribes” can become cults and then they are hard to live in for normal, healthy people. Tribe members are seen to exist to serve the “cause” or the leadership. This can describe a cult, or a fanatic political cause such as blossomed in the twentieth century. This is totally contrary to the true spirit of the tribe. A tribe should exist for the health, well-being and happiness of its tribal members. Not many should want to be part of something that makes huge demands on their freedom and productivity in order to serve some ideology. A healthy tribal existence provides things that money cannot buy: identity, solidarity and mutual loyalty. Most of the difficulties or hardships of modern life are caused by our lack of tribal life and our resultant dependence on the state— a state which increasingly does not have out best interests at heart. Not only would tribal life make the incidental difficulties easier (the car broke down, Joe will fix it) but also the great problems— alienation, isolation and loss of identity. Successful tribalism will be introduced to individuals and families gradually and in the process people will learn that life gets better and better the more they focus on their immediate environments and less on the artificial and deceptive worlds of devices and cable news.

JD: I’ve watched the beginnings of tribal culture form, and it can happen quickly — almost too quickly. Once you’ve defined a perimeter of inclusion and exclusion, people start reading the same books and sharing the same ideas and developing a framework for reality — and a humor, it often starts with humor — distinctive enough to alienate outsiders.

However, maintaining a culture over the long term seems to historically require some kind of isolation. This isolation is virtually impossible to create and maintain in the interconnected modern world without some kind of authoritarian structure. Gangs are collectively complicit in criminal acts, so they can enforce boundaries through extortion and threats of violence. Extreme religious groups and male honor groups rely on threats of “shunning” to maintain boundaries and keep people invested. How do you think the tribes that you are advocating will interact successfully with the outside world, while maintaining boundaries and a sense of cultural cohesiveness?

ET: The isolation factor you speak about is real and it is an effective aspect of forging group cohesion. Many groups do it by having beliefs that separate them from others, or a language which does so. In this day and age, such isolation has to be effected in a more subtle way. Isolation cannot be forced along. Tribes have to self-isolate because it is more practical, effective and fun to be isolated among members of one’s group than it is to mix with outsiders. That is the great challenge of the successful neo-tribalism of the future. One of the main tools in this is the implementation of what I call the Proximity Principle. Successful tribes of the future will be entirely local operations with people in the tribe living within thirty to forty miles of all other members, and mostly within a much closer proximity. If recruiting efforts are undertaken exclusively within this range, and the temptation of forming a “tribe” on Facebook or on the Internet is strictly avoided, then the social cohesion necessary for solidarity and identity to build to the level that such “self-isolation” will take place naturally and beneficially.

JD: You’ve seen a lot of groups form and disband over the years, and I’m sure you’ve witnessed your share of bad characters and organizational drama. What qualities do you think people should look for in members of a group or tribe? What qualities should they be wary of?

ET: Early on in the Asatru movement there were people who entered from nowhere and immediately started trying to “radicalize” the group. These were usually (but not always) suspected of being provocateurs or agents for the FBI or something. But less dramatically, people who enter the group and immediately start to try to change it should be suspect, and can in no way be good for the group. If they don’t like it, they should go elsewhere. In the runic world, I have sometimes been confronted by people who on the one hand are anxious to be recognized within the Rune-Gild, yet at the same time tell me that they have higher and more authentic rune-knowledge than I have to teach. I have to tell such individuals that they therefore do not need the Gild and they should teach their undefiled wisdom elsewhere. Usually that is the last I or anyone else ever hears of them. Generally, “disgruntled followers” always think they can do things better. If they do split off, they generally fail. When one is part of a crew on a functioning ship one cannot see all of the complexities the captain sees. Then if one finds one’s self as the captain of one’s own crew all of a sudden then the fact that there are a lot of missing pieces becomes obvious— and the new captain has no idea how to acquire these pieces. Exceptions to this split-off rule do exist. Sometimes the founders of movements have a good basic idea, but really are missing pieces of the vision that a later reformer can supply and the split-off is superior to the original. The Odinic universe, created after the destruction of the universe of Ymir, is, after all such a radical reformation of the status quo.

JD: Along the same lines, what qualities should people look for in a leader? And what qualities should be red flags?

ET: Some leaders seem to be ordained by the gods. They have charisma and knowledge and make their own way in the world of organizations. These are few and far between. Looking at the question from the perspective of a seeker leaders are worthy who are qualified in a world or worlds beyond their organization. Starting a group and naming yourself the grand poohbah of it is no great accomplishment. Look for leaders to be tested and certified as worthy by other parts of the world. Also, is that leader willing to relinquish power to others when appropriate or necessary. Is what is being taught or conveyed in the group 1) beneficial to life and happiness, 2) in accord with what history and tradition teaches? If so, then the leader and the group may be solid. Groups and leaders who are self-ordained, with no outside corroboration and which teaches previously unheard of ideas is probably bogus. But here as elsewhere in life, there are always exceptions.

JD: In your introduction to The Northern Dawn, you wrote about the tendency of Westerners to seek “true” wisdom from the East — “ex oriente lux.” It’s a bourgeois cliche that’s perhaps never been more pervasive. When someone wants to “get deep” or “get spiritual” they look to India or Tibet or Japan. It’s safely exotic. Obviously they are bored with the Christian approach they grew up with, but Western culture runs so much deeper than that. There is something to be gained from most traditions and practices — some kernel of wisdom — but I can’t shake the perception that so many Eastern schools lean toward the erasure of the individual and the importance of great deeds and material accomplishments. There’s something different about the Western approach. Do you see differences between Eastern and Western approaches to life? What will men find when they look to the North, that they’ll find less of in the East?

ET: I really do not see this as an originally intrinsic East/West division. It seems to have had its origins in the East round 500 BCE with the philosophy of Buddhism which began to see the world as a place filled with suffering (Sanskrit duhkha) and that the whole point of life is to annihilate the self or ego (seen as an illusion) to avoid rebirth in this world of suffering. This is a classic case of the world-denying impulse in religion and philosophy. The Indo-European philosophy is originally a world-affirming one. This was true in Vedic India, Iran as well as among all pre-Christian, indigenous European cultures. The world was seen as a good place, and cultic practices were employed to ensure the continuation of this goodness. Christianity is itself a world-denying impulse, but it is philosophically vague in this regard. The Northward view is affirming of the world, of the individual and of the culture of the tribe or society. Our strategic problem at this point is our widespread and increasing loss of collective identity and knowledge concerning our history and mythology. We have to develop our philosophies, produce material and produce teachers of the philosophy, then educate the population with all forms of media. I have forthcoming books called Our Indo-European Heritageand Our Germanic Heritage which I see as part of this effort. The sad thing is that this self-obliteration aim of Eastern religions is coming into the West at a time when many in the West are consciously or unconsciously anxious to commit cultural suicide. This self-annihilation of the individual perfectly mirrors their collective self-hating urge to obliterate their own culture, ethnos and history. There is a lot to do and new forms of media will be the vehicle for the next phase.

For a deeper look inside the mind of a modern rune master…

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”639″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://amzn.to/2m0iupa”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Would You Yet Know More?

The Rûna Interviews with Edred Thorsson – Edited By Ian Read and Michael Moynihan

from Arcana Europa / Gilded Books, 86 pages, ISBN 9781074360023